D. E. Wittkower explained friendship, along with the rise of social media, as a “caring investment in the members of our own personal communities.” At its heart, social media offers users a chance at two of life’s great desires: identity and intimacy. We get to frame our personal experience on Facebook or Twitter through every form of multimedia and continually “broadcast [this] presentation of self,” as Graham Meikle put it. Then we publicly choose who and what this self “likes” or “retweets,” and sit glued to our screens, waiting for the stream to update with more and more affirmations of commonality and connection between us and the people, things, and organizations we want in our lives — whether they are a part of our “real” lives or not.

Thus it stands to reason that a company that successfully engages its audience through social media has used content to tap into these user desires for identity and intimacy. Many have, including two that have affected my personal interest in outdoor adventure: Black Diamond Equipment and Patagonia. Though the base mission of both companies is very similar (to sell products for a profit), neither have made the mistake of using social media as a platform to sell. (This is the function of a well-designed website, among other media platforms.) Black Diamond and Patagonia have chosen to use multimedia in the social media environment as a means to build community and brand. After all, pictures of a shiny new set of skis or Gore-Tex jacket can offer a fleeting sense of identity or intimacy, but not to the extent that a genuine sense of personal, chosen community can.

For its part, Black Diamond (BD) has created a Facebook community by acknowledging that the adventures enabled by its products are more appealing to its customers than the products themselves. BD customers don’t dream of sitting on their couch, clutching their newly purchased Fusion ice tools. They dream of swinging them into fat ice at the end of a classic mixed route high in the Alps. So BD smartly offers that dream by frequently imbedding adventure videos of its sponsored athletes on its Facebook page:

Thus, as a user, I identify with this multimedia. I want that experience for myself. And by watching I have gained intimacy — with the ice axes, the Alps, and even the athletes. Another example:

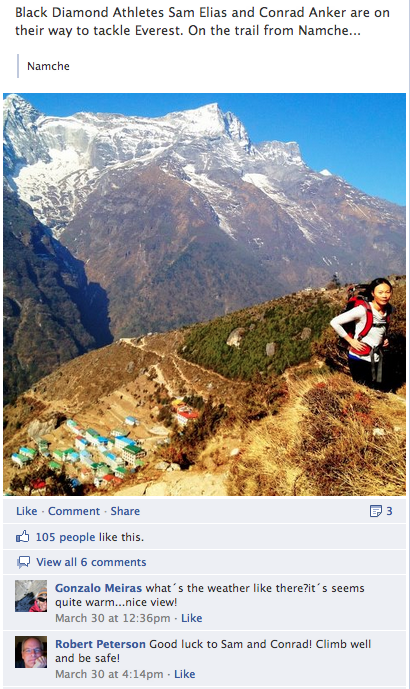

“Climb well and be safe!” exclaims one of BD’s users, clearly expressing his own attachment to the community, one that couldn’t possibly be as strong if BD used Facebook strictly for product announcements and company news. The company has identified the user’s desire to experience a great adventure and to connect with like-minded people and is using that desire to bolster its brand. Thus, personal adventure and an adventurous community become synonymous with Black Diamond. Et voila, a great brand. It’s no wonder that members of the “BD community” frequently post pictures of themselves in faraway places putting BD gear to the test (and that the company encourages this practice). They don’t feel as though they are intruding on a company’s social media campaign, but rather building a collective narrative for a community of climbers and skiers.

“Climb well and be safe!” exclaims one of BD’s users, clearly expressing his own attachment to the community, one that couldn’t possibly be as strong if BD used Facebook strictly for product announcements and company news. The company has identified the user’s desire to experience a great adventure and to connect with like-minded people and is using that desire to bolster its brand. Thus, personal adventure and an adventurous community become synonymous with Black Diamond. Et voila, a great brand. It’s no wonder that members of the “BD community” frequently post pictures of themselves in faraway places putting BD gear to the test (and that the company encourages this practice). They don’t feel as though they are intruding on a company’s social media campaign, but rather building a collective narrative for a community of climbers and skiers.

This Facebook fan communicated his experience on BD's Facebook page not just with BD, but with other BD customers. Part showing off, part sharing, he's engaged in a social interaction that is exactly similar to a personal status update or a post he might make on a friend's wall. That's a sign of genuine community, with a great byproduct of free BD product placement.

Patagonia, in many ways, has engaged in a very similar social media effort. They too have focused on community instead of product. But Patagonia suffers a major disadvantage to Black Diamond: they don’t make cool stuff. As a clothing manufacturer, Patagonia can’t elicit nearly the same level of technical nerd-dom as BD. (For example, it’s harder to imagine a Patagonia user replicating the picture above with his favorite Capilene baselayer.)

But in place of gadget lust, Patagonia has helped build its Facebook community with an even more powerful company asset: morality.

Environmentalism is woven into the fabric of the Patagonia brand, and what better place to express this core value than on Facebook, where users are constantly defining their own values and creating associations with those of similar predispositions? “Our friends and peers are crucial to the way we develop a sense of moral self-exploration,” wrote Chris Bloom on how we choose our Facebook friends, “because they have taken upon themselves the responsibility of directing our moral course.” This is precisely what Patagonia is up to here, and in the “reality” of the Facebook newsfeed, there is little, if any, difference between the moral imperative of a friend and that of an admired organization. They trickle down newsfeeds indistinguishably, gratifying our desire for identity and intimacy just the same.

Environmentalism is woven into the fabric of the Patagonia brand, and what better place to express this core value than on Facebook, where users are constantly defining their own values and creating associations with those of similar predispositions? “Our friends and peers are crucial to the way we develop a sense of moral self-exploration,” wrote Chris Bloom on how we choose our Facebook friends, “because they have taken upon themselves the responsibility of directing our moral course.” This is precisely what Patagonia is up to here, and in the “reality” of the Facebook newsfeed, there is little, if any, difference between the moral imperative of a friend and that of an admired organization. They trickle down newsfeeds indistinguishably, gratifying our desire for identity and intimacy just the same.

Is this strategy effective in building community? Look at the two comments in the picture above. Posting content on their latest snowboarding pants couldn’t possibly elicit such a personal and intimate reaction.

Patagonia and Black Diamond, like most organizations that have found success on Facebook, use multimedia content on social media platforms as a means to build community. They do this because an engaged community is the great currency of social media, where users digest multimedia as a way to affirm and expand their identities and relationships with others. (Whether those identities and intimacies are as legitimate and meaningful as those in “real life” is the subject of much debate.) Though using multimedia as tool for community building is not a new practice, it is a nearly mandatory component of the successful organizational social media effort.